A glimpse into Minnesota’s apple heritage

A unique book of notes on Minnesota’s 19th century apple varieties was recently digitized and published by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing, and it has provided apple breeders and enthusiasts a fascinating glimpse into Minnesota’s apple heritage. It is titled, simply, Apples.

Samuel B. Green became the first professor of Horticulture at the University of Minnesota in 1888. He assumed the roles of department head and fruit breeder, moving operations onto the St. Paul campus from the State Experimental Fruit Breeding Farm in Excelsior, MN, where it was initially directed by Peter Gideon, who developed the famed Wealthy apple prior to working at the University.

Amateur apple breeders across the state had been crossing and growing new apple varieties in earnest since the mid-1800s, and there were hundreds of named and unnamed varieties growing on homesteads and farms. With the establishment of the Horticulture Department, Green saw a need to inventory these varieties in order to develop a systematic breeding program.

Green compiled a volume of variety descriptions that included phenotypic observations, tasting notes, tree characteristics, growing challenges, variety ancestry when it was known, and line drawings of the fruit. Some notes came from the University’s own work, but most came from John S. Harris, an amateur breeder and long-time officer of the Minnesota State Horticultural Society.

The book was originally published in 1897, and reintroduced in 1938 by professor and department head W.H. Alderman. Researchers came across it again a few years ago in the UMN library, and found it to be an important resource for tracing the ancestry of some of our newer apple varieties. UMN librarians found it to be such a notable work that it has again been reintroduced, this time as a full-color and fully transcribed digital edition.

The book takes the reader on a kind of journey across the 19th century Minnesota landscape. One can envision farmsteads dotted with orchards filled with apples of various sizes, shapes, colors, and flavors; many more than we see today. It provides a first-hand account of the ancestors of some of Minnesota's well-known apples.

The ancestry of an apple

When you bite into a juicy Honeycrisp or bake a pie with tart Haralsons do you ever stop to think how those apples got their start? Every apple variety has ancestors just like we do, and the previous generations are the source of traits like sweetness, firmness, crispness, juiciness, skin color, disease resistance, and cold hardiness, among many others.

Like us, the children of apple tree parents have a combination of characteristics of the parents, but are never exactly like the parents. If you plant all the seeds from the apples of one tree, you’ll end up with thousands of different “child” trees that produce notably different apples with some traits similar to mom and dad, but none exactly like the two parents.

So, each variety has two parents, and of course those two parents also had parents and so on just like in our ancestry. The ancestry of all apple varieties eventually goes back to wild trees in Central Asia, since that is where the domesticated apple originated (the only apple species native to America are small fruited crabapples). Through generations of cross-pollinating and selecting the best child trees, we eventually end up with superstar varieties like Honeycrisp and SweeTango®. Along the way we had varieties in Minnesota like Lord Seedling and Sudlow’s Wax which, while no longer in existence as far as we know, played an important part in the development of varieties we know and love today.

An era of discovery and experimentation

During the 1850s and 1860s Minnesota saw a huge influx of Euro-American settlers coming West for the promise of cheap and fertile farmland. People brought with them everything they thought they would need to make a new life on the prairie, and that included fruit trees. Apples were of particular interest for their long storage life and nutrients, but also for their sugar.

“Apples provided an important source of sugar,” says Dr. Jim Luby, professor and current head of the apple breeding program at the University of Minnesota. “Cane sugar was expensive and sugar beets weren’t yet a large scale crop. Some apples were used for fresh eating, but many were used for their sugar in cooking, baked goods, and preserves. And of course they made cider...hard cider”. Plus, settlers were accustomed to certain varieties and it’s not hard to imagine that they wanted to enjoy the flavors that reminded them of home.

It took only one or two winters for people to realize that many apple varieties from Europe and the East Coast would not survive in Minnesota. Winters during the 1850s were particularly cold, and killed many of the fruit trees settlers planted.

While this was disheartening, it did not stifle the determination of these new residents. Rather, it incited a fervor of experimentation. Many homesteaders became plant breeders out of necessity, and over time developed varieties that combined winter hardiness with textures and flavors that would be suited to many uses. Varieties that had been brought from Russia and Northern Europe showed the best rates of survival, so their fruit was harvested, the seeds planted, and the seedlings grown.

Seedlings that survived the 4 to 10 years it took to reach maturity, and thus fruit production, were worthy of being named and propagated even if the flavor wasn’t ideal. Fruit that had poor flavor for fresh eating could be well-suited for cider and other uses. Variety names often honored the ‘discoverer’ of a tree, the breeder or their loved ones, highlighted a characteristic of the fruit, or even commemorated local landmarks or geographical features.

A crucial collaboration

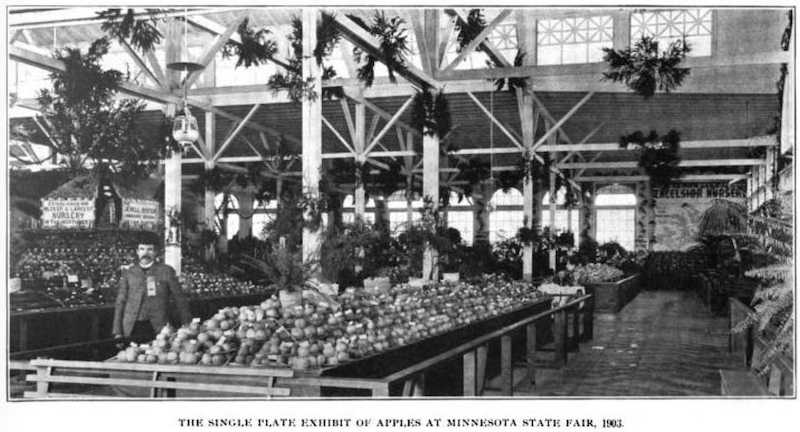

During those early years of Euro-American settlement in Minnesota, fruit growers from across the state would gather annually to display their varieties, share stories of success and failure, and discuss growing techniques. From the records kept during these gatherings, it is easy to sense a strong cooperative spirit. While there may have been some competition among growers and nurseries, Dr. Luby reminds us that “people selected and propagated hundreds of varieties just in the hopes that something would survive”.

At one of these gatherings in 1866, which took place at the Minnesota State Fair in Rochester, growers decided a more organized and concerted effort was needed if Minnesota was ever to become a true fruit growing state; so at that gathering, the Minnesota Fruit Growers Association was founded. Two years later the organization’s name was changed to the Minnesota Horticultural Society to expand efforts to other horticultural crops; and in 1873, by legislative act, the organization’s name was changed yet again to the Minnesota State Horticultural Society (MSHS) which is still going strong today.

When the Minnesota State Experimental Fruit Farm was established in 1878 under the jurisdiction of the University of Minnesota, an important partnership began. The University relied on the early work done by MSHS and its members across the state, and the two organizations worked hand in hand to improve fruit varieties and growing practices. When University fruit breeders introduced new varieties, grafted trees were sent to MSHS members around the state for trial. Members reported back with notes on tree performance, fruit quality, and challenges. These contributions were crucial to the University breeding program, and provided the foundation for successful fruit production across the state.

Harris’s variety notes that Green compiled in 1897 were a prime example of this partnership. These records provided a chronicle of what was already being grown in Minnesota, and therefore what might be valuable for breeding efforts.

Fruit breeding in the 21st century

Traditionally...well, up until just a few years ago, the process of breeding a new apple variety took anywhere from 10-30 years. These days, apple breeders at the University of Minnesota have modern tools like DNA fingerprinting to help pinpoint traits they want new varieties to include, which helps speed up the process.

There’s no genetic modification involved; it is still a totally natural process of taking pollen from one flower and brushing it onto another flower, then planting seeds from the resulting fruit to grow into new trees. But with DNA markers breeders can, for example, see how Honeycrisp’s “explosively crisp” texture carried through from previous generations. Plus, breeders can test the DNA of young seedlings for those markers so they don’t have to wait such a long time to know if a tree is going to produce good quality fruit.

Until recently, breeders had to rely solely on observations about various tree and fruit qualities, and kept detailed notes like those in Green’s book from generation to generation in an attempt to produce a tree that had the perfect combination of qualities. Breeders still use these observations today, because you can’t measure things like perceived flavor and enjoyment from an apple’s DNA.

One of the reasons that Green’s book is valuable to today’s researchers is because “it provides a documentary context for what we find with DNA fingerprinting”, explains Dr. Luby. The book was particularly valuable to Dr. Nick Howard whose PhD work resulted in the revelation of Honeycrisp’s true pedigree. He said, “the book has little information about how common the cultivars were, but it provided me with names, descriptions, and at least some context that let me know perhaps which cultivars I should seek out for genotyping.”

Dr. Howard is now in Germany in a dual post-doc position with the Carl von Ossietzky University and the University of Minnesota working on a large collaborative project involved in the identification of the pedigree connectivity between the world's most culturally, historically, and economically important apple cultivars.

Take a bite

Of course, this and other historic documents are just as fascinating for the average apple eater as they are for researchers. Take a look through Apples. As you peruse the line drawings and flowingly penned descriptions, you’ll likely find yourself craving a crisp, juicy bite of your favorite apple. As you enjoy it, pause to think about the ingenuity and determination that went into creating that variety.

And if all this has you wondering what new apple varieties might be on the horizon, you can be sure that breeders and fruit production researchers are working everyday to bring you something exciting and delicious!

Dive in deeper

Want to discover more about Minnesota’s apple varieties? Start with Minnesota Hardy, where you can explore the University of Minnesota plant breeding program and find plant varieties developed there.

Check out the University of Minnesota libraries. The catalog will help you find both historic and current publications. If you’re having trouble tracking down information, contact the library and speak to a librarian. They are amazingly helpful. Some historic documents are only available to view on-site at Magrath Library or the Andersen Horticultural Library at the MN Landscape Arboretum. This is a great experience, and you can schedule a visit by contacting the library.

The Minnesota State Horticultural Society is one of the country's oldest horticultural societies. They offer classes, lectures, webinars, special events, membership packages, volunteer opportunities, community outreach programs, and the award-winning Northern Gardener magazine.

The University of Minnesota has digitized thousands of publications that are available on the University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy (UDC). Items here are usually cross-linked from the library catalog, but you can also search directly in the UDC. Extension publications, thesis papers, research orchard records, notes, and much more can be found here.

The Hathi Trust Digital Library contains digitized versions of many of the Transactions of the Minnesota State Horticultural Society and other historic documents. Most of these are fully searchable.

Minnesota Reflections is a joint effort of the Minnesota State Historical Society, the University of Minnesota Libraries, and other organizations to digitize images and documents important to Minnesota’s history. Digitized proceedings of MN State Horticultural Society meetings can also be found here.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Dr. Jim Luby1, Dr. Nick Howard1,2, Julie Kelly3, and Dr. Emily Hoover1 for their contributions to this article.

- University of Minnesota Department of Horticultural Science, St. Paul, MN.

- Carl von Ossietzky University, Oldenburg, Germany.

- University of Minnesota Libraries, St. Paul, MN.