Grafting is defined as the fusion of plants so the resulting plant functions as a single unit. Grafting plants has been practiced for thousands of years, and this process allowed for the domestication of woody fruit trees. When the graft heals, the resulting plant has two distinct parts. The shoot system is referred to as the scion, and the root system is the rootstock. Commercially grafted apple trees consist of a single graft union between a rootstock and a scion, which is easily identified on a young tree by a distinct bulge in the trunk a few inches above the ground. From a genetic perspective, grafting involves the creation of a compound genetic system by uniting two distinct genetic systems, each of which maintains its own genetic identity throughout the life of the grafted plant.

Sometimes size is everything

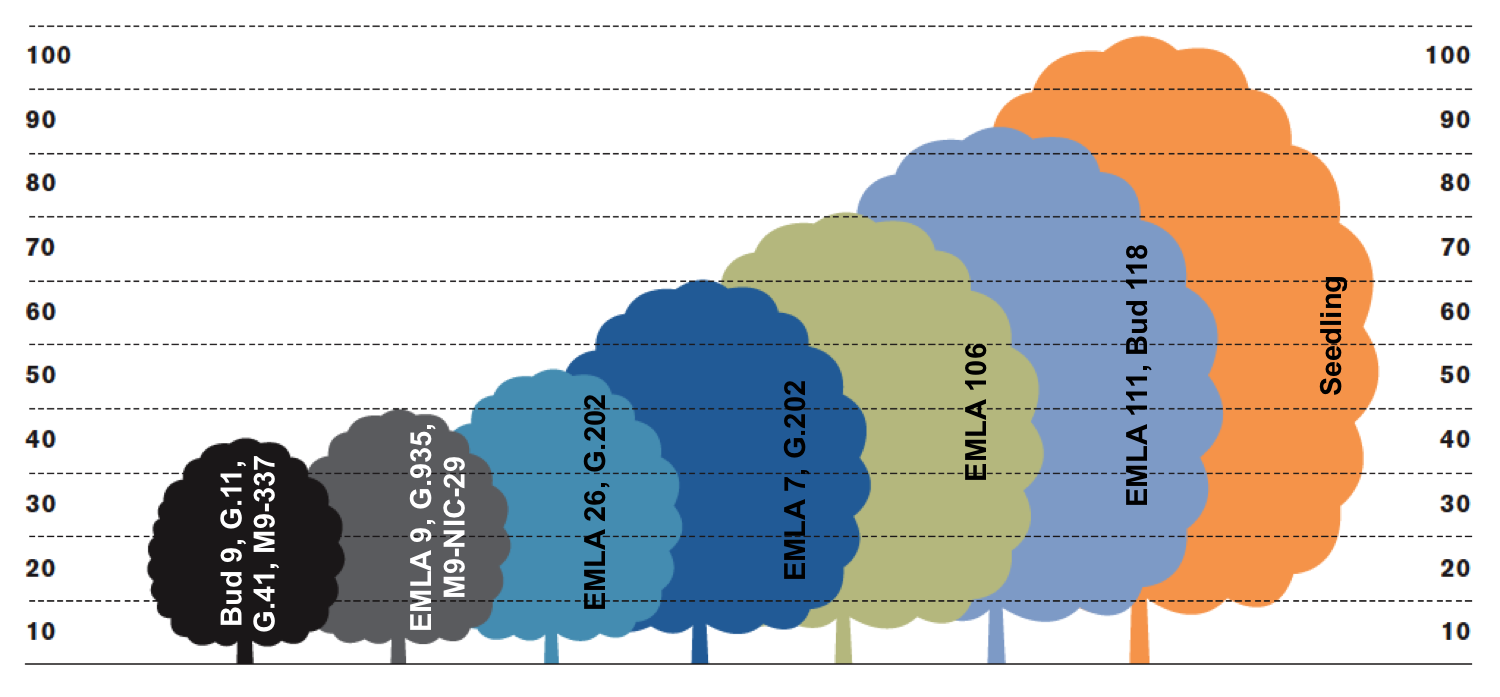

There has been a lot of research done on apple rootstocks - particularly in determining the effect of tree size and time to first harvest. Apples are one of the few fruit crops in which the rootstock has the ability to induce dwarfing of the scion cultivar. Thus, apple rootstocks are divided into groups based on the ability to dwarf the scion. Rootstocks that limit tree size to 15-45% standard are considered dwarf; 50-75% standard size are semi-dwarf; and anything above 85% is usually referred to as standard.

Smaller tree, earlier fruit

Another factor influenced by rootstock is precocity, which is the scion’s ability to bloom and produce fruit earlier in the life of the tree. This trait in rootstocks can vary the timing of the first harvest. The trend is as the rootstock induces more dwarfing, the scion will flower earlier in the life of the orchard and thus produce fruit sooner. For example, a cultivar grafted onto a dwarfing rootstock may induce flowering 5 or more years earlier in the life of the tree than the same scion on a seedling rootstock.

In search of the elusive perfect rootstock

Research done with apple rootstocks at the University of Minnesota in the Department of Horticultural Science began as part of the NC140 trial in the 1980s. The NC140 project is a group of researchers and extension educators that work together to answer questions about rootstock performance in select areas of the United States and Canada. The main objective is to evaluate the influence of rootstocks under varying environments and training systems using sustainable management practices. The apple rootstock plantings at the University of Minnesota have all been located at the Horticultural Research Center, part of the Minnesota Landscape Arboretum. Our site experiences the coldest mid-winter temperatures across all locations. The challenge of working across North America is evaluating the rootstock performance with a scion cultivar that will be able to withstand the mid-winter cold. Thus, many of the trials have used Honeycrisp as the scion since it was developed by the University of Minnesota and thus is reliably winter hardy here.

The use of this one cultivar does, however, complicate the results of the rootstock trials. Honeycrisp is known to be genetically more dwarfing than other cultivars, before even considering the effect of rootstock. Therefore the results for tree size on various rootstocks may not be directly applicable to other more vigorous cultivars. For instance, a highly dwarfing rootstock such as B.9 might be recommended for a more inherently vigorous cultivar like Zestar!®, but is not recommended for use with Honeycrisp because it induces extremely small trees. We recommend a less-dwarfing rootstock such as G. 30 for Honeycrisp as it allows the cultivar to grow vigorously in the first few years to establish a tree that can produce fruit in a fairly short period of time.

Rootstocks have many other characteristics that are considered in our research as well as in commercial and home production settings. Different rootstocks have varying degrees of influence on the tree’s longevity, productivity, tolerance of adverse soil conditions, susceptibility to certain diseases, suckering, root anchoring and breakage potential. Because there are so many factors, it’s nearly impossible to find a "perfect" rootstock. That’s why new rootstocks are continually developed, and why they are tested in so many different places. Our goal is to help farmers and gardeners find rootstocks that are appropriate for their climate and their goals.

More info on apples and apple rootstocks:

Here are some things to consider before you start an apple orchard.

University of Minnesota Extension offers practical information on growing apples in the home garden.

To find out even more about rootstocks, take a look at the articles within Apple Rootstocks: Understanding and Choosing the Right Rootstock, developed by U of M researchers and partner institutions, hosted by eXtension.org

Find details about individual rootstocks in Apple Rootstock Characteristics and Descriptions, developed by U of M researchers and partner institutions, hosted by eXtension.org.

Learn about the rootstock research being conducted by the NC-140 Regional Rootstock Research Project

References:

Mudge, K., J. Janick, S. Scofield, E.E. Goldschmidt. 2009. The History of Grafting. In: Horticultural Reviews, Volume 35. Edited by J. Janick.

Janik. E. 2011. How the apple took over the planet.