Kiwiberry is an exciting specialty crop for Minnesota that provides a tropical taste grown locally. In a previous article, we talked about a few varieties that Minnesota growers might be interested in, but when might these be ready for harvest? Harvest timing for kiwiberry depends on the variety you are harvesting and whether you are harvesting for immediate fresh eating or for larger scale commercial production of fruit that will be stored and shipped. Before we discuss harvest timing though, it is important to understand the indicators that are commonly used for identifying fruit ripening and what it means for a kiwiberry to be ripe.

When is a kiwiberry ready to eat?

A ripe kiwiberry is almost like candy with a sweet-tart taste and surprising tropical flavors. A ripe kiwiberry will have a soft feel and compress slightly when gently pinched between your fingers but will be firm enough not to split or squish. The color of the fruits will darken to a deeper green and the skin will become more translucent. These are the qualities to look for when trying to find a kiwiberry to eat fresh off the vine.

However, harvesting kiwiberry for commercial production means you have to harvest before the fruits soften. Otherwise they will be too soft to transport and protect from getting bruised and damaged. Kiwiberry can be harvested early and will continue to ripen in response to naturally produced hormones like ethylene after they are picked. Fruits that undergo this type of post-harvest ripening are referred to as climacteric fruit. So how can we know when a firm fruit will ripen after it is harvested?

Early signs of ripening for commercial production

Kiwiberries on a single plant do not all ripen at the same time, so usually the first indicator that harvest is near is the softening of a small, random portion of fruits on the vine. When walking the orchards around the end of July, we keep our eyes peeled for fallen fruit around the base of the vine. Then we start gently testing the firmness of the fruit on the vine and checking for a few soft fruits. If we feel additional soft fruit, then we know it is time to check the second indicator: seed color on the firm fruit on the vines.

Seed color and ripeness

The second sign that kiwiberries are nearing harvest readiness is the color of the seeds. The easiest way to check this is to pick a few firm berries and cut them open to examine the seed colors. Kiwiberries that have pale white or tan seeds are underdeveloped and indicate that the other fruits on the vine need more time to grow. Kiwiberries with dark brown or black seeds have reached a maturity which indicates they are likely nearing ripeness.

Testing sugar content

Before harvesting based on seed color alone, it is important that the sugar content of the fruits is examined. This is usually done by squeezing a small number of firm berries and examining the juice using a refractometer. The refractometer provides an estimation of the amount of sugar in the juice measured in °Brix. In production settings, the typical harvest recommendation for some kiwiberry varieties is between 6 and 8°Brix (Debersaques et al., 2014; Fisk et al., 2006). Once the seeds have darkened and a sample of multiple berries reads around 7-8°Brix, harvest for production can occur. Harvesting fruit before meeting these criteria means that the fruit might fail to develop in storage or their sugar content might be lower. So when might these stages be reached in different varieties?

Estimated harvest timing for different kiwiberry varieties

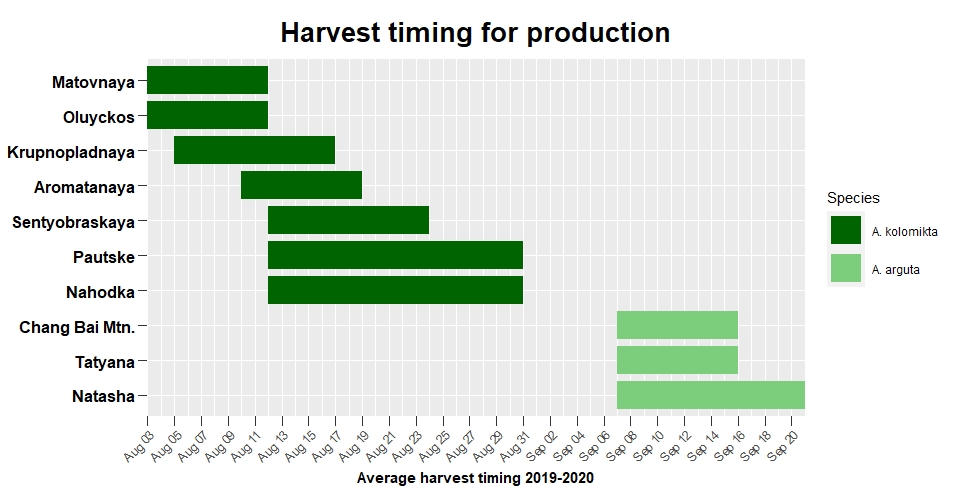

For the past couple of years, we have been harvesting kiwiberries and recording fruit qualities like firmness, storage life, weight, size, estimated sugar content, and acidity. Based on the multiple harvests of several varieties in 2019 and 2020 we have put together a timeline of when each variety is ready for harvest with the highest sugar content, size, and storage life. Of course, as with any year the environmental conditions might either speed up or delay this estimation, but on average the timeline below shows the harvest timing for ten varieties that have produced fruit at the Horticultural Research Center in Victoria, MN in 2019 and 2020.

The timeline is grouped by species because Actinidia kolomikta tend to ripen earlier in August while A. arguta ripen in early to mid-September. The earliest A. kolomikta varieties tend to be Matovnaya, Oluyckos, and Krupnopladnaya. The second grouping of earlier varieties includes Aromatanaya, Sentyobraskaya, Pautske, and Nahodka. The A. arguta varieties Chang Bai Mountain, Tatyana, and Natasha all tend to ripen in September. It should be noted that there are other varieties of A. arguta as discussed in the previous kiwiberry article, but those did not bear fruit in 2019 or 2020 due to 2019 winter damage.

This timeline is meant to help those interested in cultivating kiwiberries estimate the timing of their harvests, and will be updated as new varieties are explored!

References

Debersaques, F., O. Mekers, J. Decorte, M.C. Van Labeke, K. Schoedl-Hummel, and P. Latocha. 2014. Challenges faced by commercial kiwiberry (Actinidia arguta Planch.) Production. ActaHort. 1096: 435-442.

Fisk, C. L., M.R. McDaniel, B.C. Strik, and Y. Zhao. 2006. Physicochemical, sensory, and nutritive qualities of hardy kiwifruit (Actinidia arguta ‘Ananasnaya’) as affected by harvest maturity and storage. J. Food Sci. 71:S204-S210.

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by the Minnesota Department of Agriculture and made possible through the University of Minnesota Department of Horticultural Science.

Thank you to all the following people for their contributions to this article:

- Dr. James Luby, Professor, Department of Horticultural Science, University of Minnesota

- Dr. Robert Guthrie, Volunteer Actinidia curator, University of Minnesota

- Emily Tepe, Research associate, Department of Horticultural Science, University of Minnesota

Banner image by Seth Wannemuehler.

Any mention of or links to commercial products is for educational purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the authors, the University of Minnesota, the Minnesota Department of Agriculture, nor any other organization supporting this research.